Insights

Please Wait

Capturing and Sharing Insights

Having the right information can save hours of work and frustration, but a lot of this valuable knowledge is not found in textbooks, taught in classes, or easily located by searching online sources. Much of this knowledge is gained through experience and trapped in the minds and lab notebooks of people working in the world of photonics.

Thorlabs is on a mission to collect these tips, tricks, guidelines, and practical techniques into a book of knowledge we call Insights. Click on the following links or browse the tabs on this page to read the Insights we have recorded as of today. This collection is always growing, so check back soon to see what new Insights have been added.

The Field of Photonics

- What is photonics?

Alignment of Optical Components

- What is a procedure for correcting a laser's beam pointing angle?

- How are two mirrors used to align a laser beam along a different path?

- What is the required spacing between two beam-steering mirrors?

Beam Expanders

- What is an example of a do-it-yourself Keplerian beam reducer?

- Can expanding a laser beam effectively create a smaller beam size?

- Does it matter whether a beam expander or reducer has a Keplerian or Galilean design?

Best Lab Practices

- Clamping Forks: Tip for Maximizing the Holding Force

- Optical Tables: Clamping Forks and Distortion of the Table's Surface

- Washers: Using Them with Optomech

- Electrical Signals: AC vs. DC Coupling

- Fiber Collimators: Tip for Mounting with Adapter

- How are the large mounting holes (counterbores) at the middle of a translation stage used?

- Is fast access to all mounting slots on a linear translation stage possible?

- What are some first steps to improving power measurements of low-power optical signals?

Collimation

- Does collimated light maintain a constant beam diameter out to infinity?

- Is the beam spot output by a collimating lens an image of the lamp or LED source?

Design Elements of Thorlabs' Products

- Do translation stages isolate mounted components from vibrations transmitted through the adjuster?

- Post Holders: Rectangular Channel in the Inner Bore

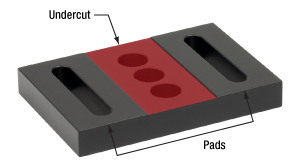

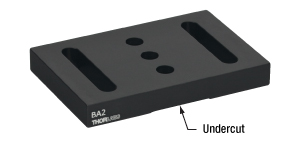

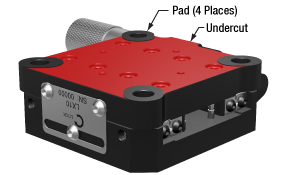

- Bases: For Stability Orient the Side with the Undercut Down

Fiber Optics

- When does NA provide a good estimate of the fiber's acceptance angle?

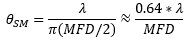

- Why is MFD an important coupling parameter for single mode fibers?

- Does NA provide a good estimate of beam divergence from a single mode fiber?

- What factors affect the amount of light coupled into a single mode fiber?

- Is the max acceptance angle constant across the core of a multimode fiber?

Imaging

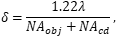

- Does the condenser's NA affect the microscope's resolution?

- How does Köhler illumination work in microscopy?

Integrating Spheres

- Ultraviolet and Blue Fluorescence Emitted by Integrating Spheres

- Sample Substitution Errors

Lasers

- Are collimated beams always emitted parallel to the laser's axis?

- Quantum and Interband Cascade Lasers (QCLs and ICLs): Operating Limits and Thermal Rollover

- HeNe Lasers: Handling and Mounting Guidelines

- Beam Size Measurement Using a Chopper Wheel

- Can the thin-lens equation be used with laser light?

Lens Mounts

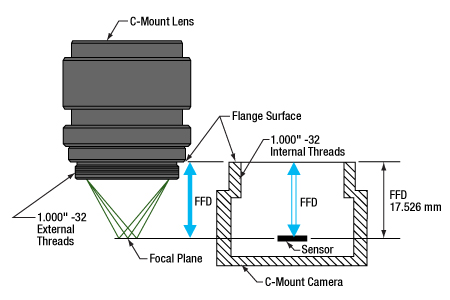

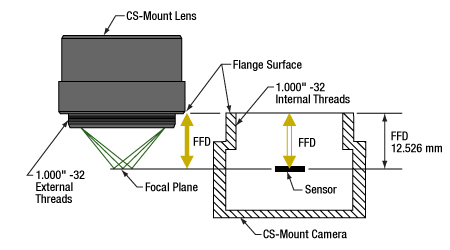

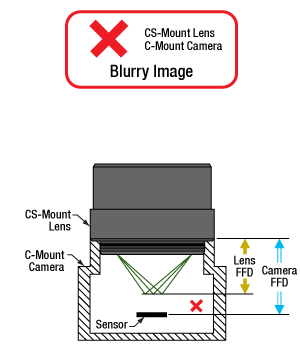

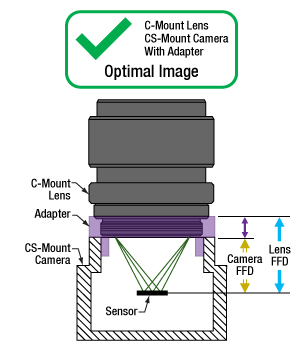

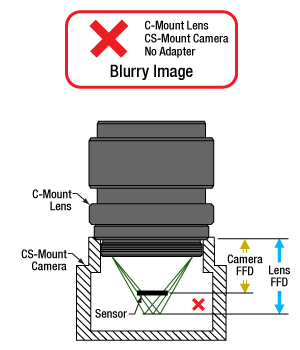

- Can C-mount and CS-mount cameras and lenses be used with each other?

- Do Thorlabs' scientific cameras need an adapter?

- Why can the FFD be smaller than the distance separating the camera's flange and sensor?

Motion Control

- How can a manual translation stage be motorized?

- Recording Position from Digital Micrometers

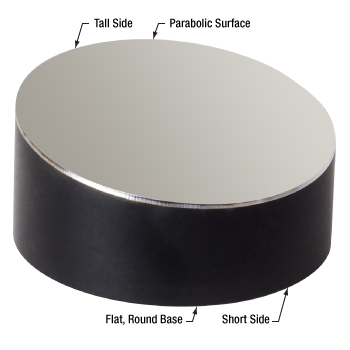

Off-Axis Parabolic (OAP) Mirrors

- Why use a parabolic mirror instead of a spherical mirror?

- Benefit of an Off-Axis Parabolic Mirror

- The Off-Axis Angle of an OAP Mirror

- Focus Collimated Light / Collimate Light from a Point Source Using an OAP Mirror

- Locating the Optical and Focal Axes of an OAP Mirror

- Paired OAP Mirrors Can Relay an Image and Make the Beam Accessible

- Mounting and Aligning an OAP Mirror

- Directionality of OAP-Mirror-Based Reflective Collimators

Optical Isolators and the Faraday Effect

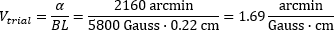

- How can the strength of a material's Faraday effect be measured?

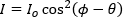

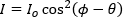

- What is needed to determine the direction and magnitude of the Faraday rotation angle?

Photodiodes

- How does wavelength affect rise time?

Polarization-Maintaining (PM) Fiber

- Does PM fiber preserve every input polarization state?

- How does polarization-maintaining fiber preserve linearly polarized light?

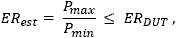

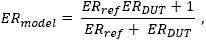

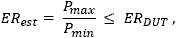

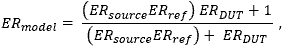

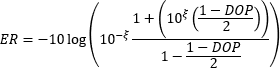

- What limits the extinction ratio (ER) of light output from PANDA and bow-tie PM fibers?

- What is beat length and why is it often specified for PM fiber, instead of polarization extinction ratio?

- Are polarization-maintaining fibers with stress rods affected by operating temperature?

Polarized Light

- Labels Used to Identify Perpendicular and Parallel Components

- How is the polarization ellipse related to the polarization state?

- How is a Poincaré sphere useful for representing polarization states?

- Can the extinction ratio of a polarizing component be measured using an unpolarized light source?

- Can a linearly polarized light source be used to measure the extinction ratio of a polarizing optic?

Reflective Elements

- Is there a rule for choosing the mirror's diameter based on the laser beam's diameter?

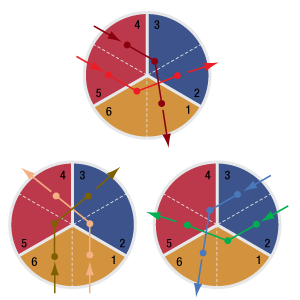

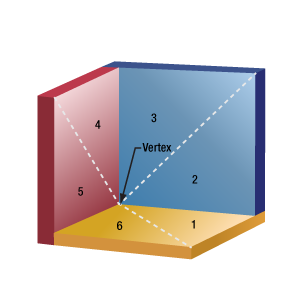

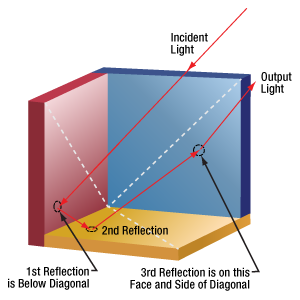

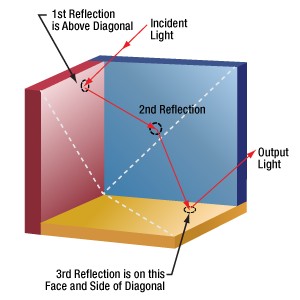

- How does alignment affect the beam path through a retroreflector?

- Why coat the backsides of solid prism retroreflectors with metal?

- Does the angle of incidence affect the output beam power from a corner-cube retroreflector?

Software and Writing Programs to Control Devices

- DM713 Digital Micrometer: LabVIEW and C# Programming References

Video Insights

- How to Align a Laser

- Optical Power Meter Parameter Setup for Improved Accuracy

- How to Motorize a Manual Translation Stage

- Tips for Bolting Post Holders to Optical Tables, Bases, and Breadboards

- How to Align an Optical Isolator

- Align a Linear Polarizer's Axis to be Vertical or Horizontal to the Table

- Cleave a Large-Diameter Silica Fiber Using a Hand-Held Scribe

- Measure the Insertion Loss of a Fiber Optic Component

- Create Circularly Polarized Light Using a Quarter-Wave Plate (QWP)

- Align a Linear Polarizer 45° to the Plane of Incidence

- Align Fiber Collimators to Create Free Space Between Single Mode Fibers

- Setting Up a TO Can Laser Diode (Viewer Inspired)

- Setting Up a Pigtailed Butterfly Laser Diode (Viewer Inspired)

- Distinguish the Fast and Slow Axes of a Quarter-Wave Plate

- Visual Studio® Project Setup and C# Programming - Kinesis® BBD300 Series Controller

- Build a Polarimeter to Find Stokes Values, Polarization State (Viewer Inspired)

- Raster Scan Using Visual Studio® and C# Programming- Kinesis® BBD300 Series

- Align an Off-Axis Parabolic (OAP) Mirror to Collimate a Beam (Viewer Inspired)

- Camera Setup and Image Acquisition Using Visual Studio® and C# Programming

- Align FiberPorts on a FiberBench (Viewer Inspired)

- Working with KF (QR) Vacuum Flange Components

- Mounting your Optomech: Bases, Post Holders, and Posts

- Use Laser Speckle to Find the Beam Focus

- Python® Automation of a Power Meter and Rotation Mount (Viewer Inspired)

- Working with CF Vacuum Flanges

- Calibrate a Spatial Light Modulator (SLM) for Phase Delay (Viewer Inspired)

- Collimate a Laser with a Shear-Plate Collimation Tester (Viewer Inspired)

- PM Fiber Coupling Methods to Align Incident Polarization (Viewer Inspired)

- Herriott Cell Setup and Configuration (Viewer Inspired)

- Collimate Light from an LED

- Build a Solar Imaging Telescope with Tracking Capability

- How Light’s Incident Angle Affects Transmission & Finding Brewster’s Angle

What is Photonics?

|

Photonics is the study and use of light. The word photonics is based on a “photon”, which is a single particle of light. This is similar to electronics where the electrons are single particles of charge that make up electric current. In photonics, the photons are single particles of energy that make up light. The amount of energy provided by a photon depends on the color (wavelength). For example, a laser pointer that outputs 1 mW of red (640 nm) light provides Light is generated by a variety of sources. Some come from nature, like the sun, fire, or bioluminescence (lightning bugs). Manufactured sources include light bulbs, LEDs, and lasers. Much like wires are used to transport electric current, photonics uses optical fiber to transport light from one location to another. |

Similar to electronics using resistors and capacitors to modify the current flow through a circuit, photonics uses optics like lenses, mirrors, and prisms to direct and modify light paths. Almost all analysis of light is done with the same measurement equipment used in electronics, but a device is required to first convert the photons into electrical current. Common uses for photonics are to measure distance (laser radar), transmit/receive information (telecommunications), image objects that are difficult to see by the eye alone (microscopes / endoscopes / borescopes), and create sensors such as the amount of oxygen in the blood (pulse oximeters) and the quality of the air around us (particle size and trace gas detection). |

Date of Last Edit: Apr. 20, 2022

Insights into Techniques for Aligning and Routing Laser Beams

Scroll down to read about motivations, techniques, and rules for aligning and routing collimated laser beams.

- What is a procedure for correcting a laser's beam pointing angle?

- How are two mirrors used to align a laser beam along a different path?

- What is the required spacing between two beam-steering mirrors?

What is a procedure for correcting a laser's beam pointing angle?

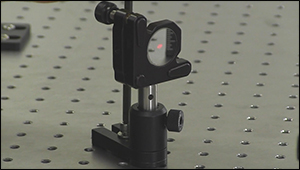

Pitch (tip) and yaw (tilt) adjustments provided by a kinematic mount can be used to make fine corrections to a laser beam's angular orientation or pointing angle. This angular tuning capability is convenient when aligning a collimated laser beam to be level with respect to a reference plane, such as the surface of an optical table, as well as with respect to a particular direction in that plane, such as along a line of tapped holes in the table.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 2: The beam can be aligned to travel parallel to a line of tapped holes in the optical table. The yaw adjustment on the kinematic mount adjusts the beam angle, so that the beam remains incident on the ruler's vertical reference line as the ruler slides along the line of tapped holes.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 1: Leveling the beam path with respect to the surface of an optical table requires using the pitch adjustment on the kinematic laser mount (Figure 2). The beam is parallel to the table's surface when measurements of the beam height near to (left) and far from (right) the laser's front face are equal.

Video Clip 3: The pointing angle of a laser beam from a PL202 collimated laser package was corrected using the pitch (tip) and yaw (tilt) adjusters on the laser's KM100 kinematic mount, and horizontal and vertical features on a BHM1 ruler. The resulting beam travels parallel to the optical table's surface, along a line of tapped holes.

Before Using the Mount's Adjusters

First, rotate each adjuster on the kinematic mount to the middle of its travel range. This reduces the risk of running out of adjustment range, and the positioning stability is frequently better when at the center of an adjuster's travel range.

Then, make coarse corrections to the laser's height, position, and orientation. This can be done by adjusting the optomechanical components, such as a post and post holder, supporting the laser. Ensure all locking screws are tightened after the adjustments are complete.

Level the Beam Parallel to the Table's Surface

Leveling the laser beam is an iterative process that requires an alignment tool and the fine control provided by the mount's pitch adjuster.

Begin each iteration by measuring the height of the beam close to and far from the laser (Figure 1). A larger distance between the two measurements increases accuracy. If the beam height at the two locations differs, place the ruler in the more distant position. Adjust the pitch on the kinematic mount until the beam height at that location matches the height measured close to the laser. Iterate until the beam height at both positions is the same.

More than one iteration is necessary, because adjusting the pitch of the laser mount adjusts the height of the laser emitter. In Clip 3 for example, the beam height close to the laser was initially 82 mm, but it increased to 83 mm after the pitch was adjusted during the first iteration.

If the leveled beam is at an inconvenient height, the optomechanical components supporting the laser can be adjusted to change its height. Alternatively, two steering mirrors can be placed after the laser and aligned using a different procedure. Steering mirrors are particularly useful for adjusting beam height and orientation of a fixed laser.

Orient the Beam Along a Row of Tapped Holes

Aligning the beam parallel to a row of tapped holes in the table is another iterative process, which requires an alignment tool and tuning of the mount's yaw adjuster.

The alignment tool is needed to translate the reference line provided by the tapped holes into the plane of the laser beam. The ruler can serve as this tool, when an edge on the ruler's base is aligned with the edges of the tapped holes that define the line (Figure 2).

The relative position of the beam with respect to the reference line on the table can be evaluated by judging the distance between the laser spot and vertical reference feature on the ruler. Vertical features on this ruler include its edges, as well as the columns formed by different-length rulings. If these features are not sufficient and rulings are required, a horizontally oriented ruler can be attached using a BHMA1 mounting bracket.

In Clip 3, when the ruler was aligned to the tapped holes and positioned close to the laser, the beam's edge and the ends of the 1 mm rulings coincided. When the ruler was moved to a farther point on the reference line, the beam's position on the ruler was horizontally shifted. With the ruler at that distant position, the yaw adjustment on the mount was tuned until the beam's edge again coincided with the 1 mm rulings. The ruler was then moved closer to the laser to observe the effect of adjusting the mount on the beam's position. This was iterated as necessary.

Want additional Insights on beam alignment?

Watch the full video.

Date of Last Edit: Oct. 12, 2020

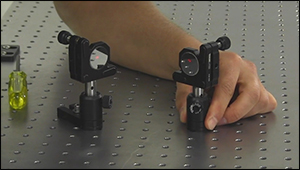

How are two mirrors used to align a laser beam along a different path?

The first steering mirror reflects the beam along a line that crosses the new beam path. A second steering mirror is needed to level the beam and align it along the new path. The procedure of aligning a laser beam with two steering mirrors is sometimes described as walking the beam, and the result can be referred to as a folded beam path. In the example shown in Clip 4, two irises are used to align the beam to the new path, which is parallel to the surface of the optical table and follows a row of tapped holes.

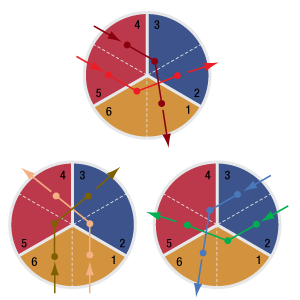

Click to Enlarge

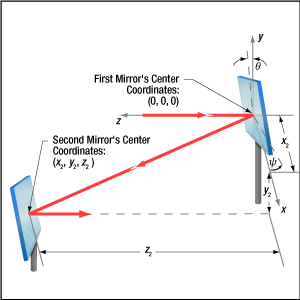

Figure 3: The beam reflected from Mirror 1 will be incident on Mirror 2, if Mirror 1 is rotated around the x- and y-axes by angles θ and ψ, respectively. Both angles affect each coordinate (x2 , y2 , z2 ) of Mirror 2's center. Mirror 1's rotation around the x-axis is limited by the travel range of the mount's pitch (tip) adjuster, which limits Mirror 2's position and height options.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 5: The adjusters on the second kinematic mirror are used to align the beam on the second iris.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 4: The adjusters on the first kinematic mirror mount are tuned to position the laser spot on the aperture of the first iris.

Video Clip 4: Two mirrors in KM100 kinematic mounts route the beam from a PL202 collimated laser package along the path defined by the two IDA25 irises. The beam is aligned when halos of laser light surround each iris' aperture and the laser spot is visible on the BHM1 ruler, which was placed behind the second iris to act as a viewing screen.

Setting the Heights of the Mirrors

The center of the first mirror should match the height of the input beam path, since the first mirror diverts the beam from this path and relays it to a point on the second mirror. The center of the second mirror should be set at the height of the new beam path.

Iris Setup

The new beam path is defined by the irises, which in Clip 4 have matching heights to ensure the path is level with respect to the surface of the table. A ruler or calipers can be used to set the height of the irises in their mounts with modest precision.

When an iris is closed, its aperture may not be perfectly centered. Because of this, switching the side of the iris that faces the beam can cause the position of the aperture to shift. It is good practice to choose one side of the iris to face the beam and then maintain that orientation during setup and use.

Component Placement and Coarse Alignment

Start by rotating the adjusters on both mirrors to the middle of their travel ranges. Place the first mirror in the input beam path, and determine a position for the second mirror in the new beam path (Figure 3). The options are notably restricted by the travel range of the first mirror mount's pitch (tip) actuator, since it limits the mirror's rotation (θ ) around its x-axis. In addition to the pitch, the yaw (tilt) of the first mirror must also be considered when choosing a position

After placing the second mirror on the new beam path, position both irises after the second mirror on the desired beam path. Locate the first iris near the second mirror and the second iris as far away as possible.

While maintaining the two mirrors' heights and without touching the yaw adjusters, rotate the first mirror to direct the beam towards the second mirror. Adjust the pitch adjuster on the first mirror to place the laser spot near the center of the second mirror. Then, rotate the second mirror to direct the beam roughly along the new beam path.

First Hit a Point on the Path, then Orient

The first mirror is used to steer the beam to the point on the second mirror that is in line with the new beam path. To do this, tune the first mirror's adjusters while watching the position of the laser spot on the first iris (Figure 4). The first step is complete when the laser spot is centered on the iris' aperture.

The second mirror is used to steer the beam into alignment with the new beam path. Tune the adjusters on the second mirror to move the laser spot over the second iris' aperture (Figure 5). The pitch adjuster levels the beam, and the yaw adjuster shifts it laterally. If the laser spot disappears from the second iris, it is because the laser spot on the second mirror has moved away from the new beam path.

Tune the first mirror's adjusters to reposition the beam on the second mirror so that the laser spot is centered on the first iris' aperture. Resume tuning the adjusters on the second mirror to direct the laser spot over the aperture on the second iris. Iterate until the laser beam passes directly through the center of both irises (Clip 4). If any adjuster reaches, or approaches, a limit of its travel range, one or both mirrors should be repositioned and the alignment process repeated.

If a yaw axis adjuster has approached a limit, note the required direction of the reflected beam and then rotate the yaw adjuster to the center of its travel range. Turn the mirror in its mount until the direction of the reflected beam is approximately correct. If the mirror cannot be rotated, reposition one or both mirrors to direct the beam roughly along the desired path. Repeat the alignment procedure to finely tune the beam's orientation.

If a pitch axis adjuster has approached a limit, either increase the two mirrors' separation or reduce the height difference between the new and incident beam paths. Both options will result in the pitch adjuster being positioned closer to the center of its travel range after the alignment procedure is repeated.

Want additional Insights on beam alignment?

Watch the full video.

Date of Last Edit: Oct. 22, 2020

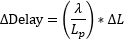

What is the required spacing between two beam-steering mirrors?

The required separation between two steering mirrors (Figure 6) depends on the slope of the beam reflected from the first mirror and the height difference between the two mirrors. Knowing the needed spacing can be important for blocking out space for a setup on a breadboard or optical table.

While it is tempting to perform a quick calculation using just the first mirror's pitch (tip) with respect to the incident beam, omitting the yaw (tilt) can result in a significant underestimate of the mirrors' required separation. In the following example, the spacing is calculated using the assumption that the entire mount is rotated around the post axis to provide yaw, while the mount's adjuster provides pitch (Figure 7). This approach is often used to initially position mirrors.

Click to Enlarge

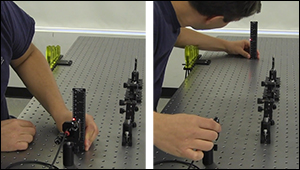

Figure 7: Instead of using the yaw adjuster, the entire mount is often rotated around the post axis (left) to provide yaw during initial positioning. This rotates the mount with respect to the global x-, y-, z-axes and the incident beam. The mount's pitch adjuster tunes the mirror's pitch (right), changing the mirror's orientation with respect to the mount's x'-, y'-, and z'-axes. The above images show a KS2 mirror mount and a RMC position-maintaining collar.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 6: The first mirror reflects the incident beam towards the second mirror. The required spacing between the two depends on both the pitch and yaw of the first mirror. These KM100 mirror mounts have adjusters that can tune pitch and yaw over a ±4° range.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 9: These values were calculated using the setup described in Figure 8, except that a 1° pitch angle was assumed for the first mirror. These results demonstrate that decreasing the pitch increases the required separation between the first and second mirrors. However, this may be acceptable since stability improves when the adjusters are not extended to the limits of their travel ranges.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 8: In this example, the goal is to position the second mirror on the table, so that it intercepts the reflected beam when it is 0.5" lower (y2 = -0.5") than the incident beam. It is assumed the pitch on the first mirror is 4°, the maximum the mount's adjuster can provide. The entire mount is rotated around the post axis to change the first mirror's yaw. The mount's yaw adjuster is not used, since yaw angles >4° are of interest and this step does not involve fine-tuning the mirror's orientation.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 10: This plot views the table's surface from above, with the first mirror (star) at the origin. Curves labeled in the legend identify a few options for positioning a second mirror on the table to intercept the beam at a height (y2) that is 0.5" lower than at the first mirror. The required separation increases significantly as the first mirror's yaw angle increases, even when its pitch angle is held constant.

Applying Yaw and Pitch

Positioning beam steering mirrors is typically a two-step process. First the mirrors are placed in position and roughly oriented, then their orientations are finely tuned.

This example considers the first step and assumes different methods are used to adjust pitch and yaw. Since the required yaw angle is often too large for the mount's adjuster to provide, yaw is frequently provided by rotating the entire mount around the post axis (Figure 7, left). This changes the incident beam's angle with respect to the mount. Although the mount's yaw adjuster is not used, the pitch adjuster is used. It alters the orientation of the mirror with respect to both the incident beam and the rest of the mount (Figure 7, right).

The mirror's orientation is typically fine-tuned using the mount's pitch and yaw adjusters, without rotating the mount around the post axis. Using both adjusters has a different effect on the mirror's orientation than the approach described in this example.

Points on the Reflected Beam

The first mirror's center is chosen as the origin of a fixed Cartesian coordinate system (Figure 7). The z-axis points back towards the source and is parallel to the incident beam. The y-axis is vertical and perpendicular to the table.

Points on the Reflected Beam

The first mirror's center is chosen as the origin of a fixed Cartesian coordinate system (Figure 2). The z-axis points back towards the source and is parallel to the incident beam. The y-axis is vertical and perpendicular to the table.

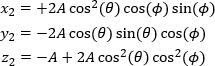

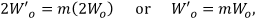

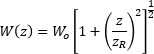

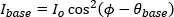

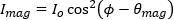

When the angles of rotation around the post and x'-axes are known ( and θ, respectively), points

and θ, respectively), points

.

.

The variable A is a scaling factor: the larger its value, the larger the distance between the point and the mirror. In this example, the change in height (y2 ) is known and used to calculate values of x2 and z2 .

Example: Setting up Steering Mirrors

These equations can be useful when positioning a pair of steering mirrors, which are used to change beam height and direction. The center of the first mirror is set at the height of the incident beam, and the center of the second mirror is set at the height of the new beam path. The second mirror must intercept the reflected beam when its height equals that of the new beam path.

For this example, both beam paths are parallel to the optical table, but the new beam path is 0.5" lower than the incident beam path. The mirrors are secured in KM100 kinematic mounts, which are attached to the tops of posts secured in post holders (Figure 6). The mounts' pitch and yaw adjusters each have a limited ±4° tuning range, which is adequate for setting the initial pitch, but not yaw, of the mirror. The yaw between the incident beam and mirror is instead changed by rotating the entire mount around the post axis, which effectively eliminates the yaw tuning range limit.

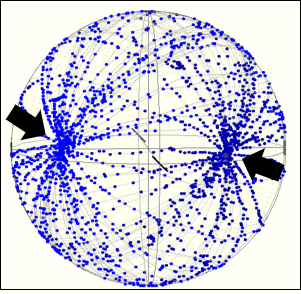

Potential x2 and z2 coordinates of the second mirror are plotted in Figure 8 for different yaw angles of the first mirror. These values were calculated using the desired height change of the new beam path

Figure 10 plots the x2 and z2 coordinates of the second mirror as positions on the optical table. The perspective is from a point directly above the table, the first mirror's position is marked by a star, and the gray circles (guides for the eye) are concentric around it. The arrows indicate selected directions of the reflected ray, each corresponding to a different yaw angle. The curves labeled in the legend were calculated for different pitch angles and a constant -0.5" change in beam height. Comparing the curves with the gray circles illustrates that the necessary separation between the two mirrors increases significantly as the yaw angle increases. Larger separations are also required when the pitch angle is reduced.

Want additional Insights on beam alignment?

Watch the full video.

Date of Last Edit: Jan. 5, 2021

Insights into Beam Expanders

Scroll down to read about collimation and collimated beams. Collimation is used to reduce the divergence of light from narrowband laser sources with Gaussian beam profiles, as well as from broadband and white-light sources such as light emitting diodes (LEDs) and bulbs.

- What is an example of a do-it-yourself Keplerian beam reducer?

- Can expanding a laser beam effectively create a smaller beam size?

- Does it matter whether a beam expander or reducer has a Keplerian or Galilean design?

What is an example of a do-it-yourself Keplerian beam reducer?

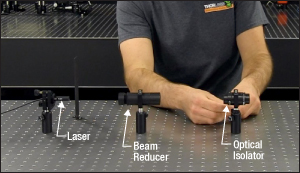

A beam reducer was designed and constructed for placement between a low-power continuous wave (CW) laser and a free-space optical isolator. The laser's wavelength was within the isolator's operating range, but the beam diameter exceeded the isolator's maximum specification. The design of the beam reducer was based on a Keplerian telescope and constructed using two positive lenses.

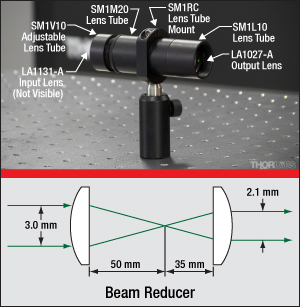

Click to Enlarge

Figure 1: A Keplerian beam reducer was designed and constructed to reduce the diameter of a laser beam, which was required to pass through an optical isolator's input and output apertures without clipping.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 2: This beam reducer was fabricated using two positive focal length lenses separated by the sum of their focal lengths. The reduction ratio equaled the focal length of the output lens divided by the focal length of the input lens. The labeled components (top) were used to assemble the beam reducer, and the output beam diameter was adjusted by measuring it while adjusting the SM1V10 lens tube length.

Beam Diameter Requirements

The laser source was a PL201, which outputs a CW and collimated beam with a wavelength of 520 nm and typical optical output power of 0.9 mW. At a distance 5 cm from the laser, a circle 3 mm in diameter would contain over 99% of the beam's power.

However, a specification for the free-space optical isolator

Reduction Ratio and Lens Choice

Beam reducer designs are often based on two-lens Keplerian or Galilean telescopes. Both approaches would provide similar performance in this application, but a Keplarian design was chosen to take advantage of the ease of using ray tracing geometry to graphically block out lens placements and show the output beam diameter (Figure 2, bottom).

Plano-convex lenses with 1" diameters, anti-reflective coatings, and positive focal lengths were chosen. Selecting lenses with large clear apertures compared with the beam diameter minimized aberrations, as did orienting the lenses so that their curved sides faced collimated beams and their flat sides faced the beam focus (Figure 2, bottom). In addition, 1" diameter optics are directly compatible with 1" diameter lens tubes and related accessories.

The target reduction ratio

Effect of Beam Reduction on Divergence Angle

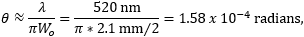

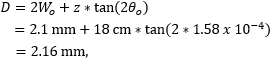

A beam reducer shrinks the diameter of the beam waist but increases the divergence angle. Although the beam diameter would be 2.1 mm near the output face of the beam reducer, diffraction effects would cause the beam diameter to increase as it propagates. In this application, the beam diameter must be less than 2.7 mm in diameter after propagating across ~18 cm of free space to enter the isolator without clipping.

To investigate whether the reduced beam would meet the isolator's input diameter specification and travel through the isolator without clipping, the laser beam's waist diameter

is the wavelength of the laser light

is the wavelength of the laser light

at the input to the isolator. The distance used in the equation was then increased

Construction

The ideal beam reducer design (Figure 2, bottom) assumes the input beam waist is one focal length (50 mm) away from the curved input side of the left lens. Under these conditions, the light focuses to a point that is one focal length away from the planar output side of the lens, as illustrated. When this input condition is not met, which is the case in this work, the focal point of the beam output by the first lens will not be exactly 50 mm away, and the diameter of the beam provided by the beam reducer will differ from the ideal calculated value. In order for the beam reducer to provide the specified beam diameter over the required distance, it may be necessary to adjust the spacing between the two lenses from the ideal design values. In this application, the housing was constructed to allow this spacing to be tuned.

The housing that secured and positioned the two lenses approximately 85 mm (3.4") apart from each other was constructed using lens tubes (Figure 2). As seen in this figure, the curved sides of the lenses faced the directions of the collimated light. A 3" tube was fabricated by attaching two fixed-length lens tubes, 1" (SM1L10) and 2" (SM1M20) together. The 35 mm lens was secured within the 1" lens tube. An adjustable lens tube (SM1V10), which held the 50 mm focal length lens, supplied the required additional length and allowed the distance between the two lenses to be optimized. The assembly was held in a lens tube mount (SM1RC) during the alignment of the isolator.

Want to see how this beam reducer was used?

Watch the full video.

Date of Last Edit: June 18, 2021

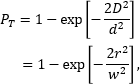

Can expanding a laser beam effectively create a smaller beam size?

Since a beam expander converts an input beam with a smaller waist and larger divergence into an output beam with a larger waist and smaller divergence, the output beam can have a smaller diameter far from the beam expander when compared with the input beam. The beam diameter does not remain constant with distance due to the effects of diffraction. As the beam divergence is higher for beams with smaller waists, using a beam expander to increase the waist diameter is a technique for reducing the rate at which the beam diameter increases as the beam propagates away from its waist. Beam expanders are often used to reduce beam divergence and ensure the beam diameter does not exceed a specified limit at distances far from the output beam waist.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 3: The input beam has a smaller waist diameter than the output beam. However, the diameter of the smaller input beam changes at a substantially higher rate than the larger output beam. Within the limited range shown above, the diameter of the input beam exceeds that of the output beam.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 4: A beam has a nearly constant divergence angle far from the beam waist. As described in the text, this angle

Beam Expanders (and Reducers)

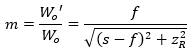

Beam expanders (and beam reducers) accept a collimated beam with one waist diameter and provide a collimated beam with a different waist diameter. The expansion ratio, or magnification (m ),

relates the diameters of the beam waists before

Measuring the beam cross sections at the input and output beam waist locations can provide estimates of the waist diameters. The manufacturer often specifies the output beam waist location, but if it is not known, a measurement of the beam diameter close to the output of the beam expander can be used to approximate the waist diameter.

Beam Divergence

A laser beam's diameter is always smallest at its waist. Away from the waist, the beam diameter increases due to the effects of diffraction, and this rate of increase is the beam's angular divergence. Far from the beam waist, the divergence angle is approximately constant (Figure 4). An estimate of this divergence angle

can be calculated from the wavelength  )

)

The difference in the angular divergence of the beams input to and output from a beam expander or reducer can be estimated using the beam expansion ratio

in which θin and θout are the divergence angles of the input and output beams, respectively, far from their beam waists.

In the case of a beam expander

A beam reducer

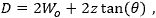

Avoid Beam Clipping

The diameter of the output beam close to the beam expander is often a good approximation of the output beam waist diameter. Farther away, the beam diameter may have increased enough to cause beam clipping or other unintended effects. Calculating estimates of the beam diameter

at critical distances

Date of Last Edit: Aug. 23, 2021

Content improved by our readers!

Does it matter whether a beam expander or reducer has a Keplerian or Galilean design?

The design of the beam expander or reducer does not always matter to the application, but the choice can be influenced by factors such as the easier alignment and more intuitive design of the Keplerian devices and the compact dimensions of the Galilean devices. Additionally, a Keplerian device focuses the light between its two lenses and then outputs an inverted beam. A Galilean device maintains the orientation of the beam and provides the option to select lenses to reduce the amount of spherical aberration in the output beam.

Beam expanders and reducers are typically used only with collimated beams, rather than diverging beams, and these designs take their inspiration from Keplerian and Galilean telescopes. The magnification provided in both cases equals the focal length of the output lens divided by the focal length of the input lens.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 5: The simplest Keplerian beam expander or reducer includes two positive lenses. The focal lengths of Lens 1 and Lens 2 are f1 and f2, respectively. The lenses are separated by a distance equal to the sum of their focal lengths

Click to Enlarge

Figure 6: A basic Galilean beam expander or reducer includes a negative lens with focal length

Characteristics of the Keplerian Design

In the simplest Keplerian design, two positive lenses are separated by a distance equal to the sum of their focal lengths (Figure 5). A design based on the Keplerian telescope will never be shorter than the sum of the two lenses' focal lengths, and the output beam is inverted with respect to the input beam.

The beam comes to a focus between the two lenses. This provides the opportunity to spatially filter the beam. For example, a pinhole filter could be placed at the beam's focal point to improve beam quality. Away from the focus, the beam diameter expands as it approaches the output lens. To increase the diameter of the collimated beam provided by the output lens, it is necessary to move the output lens farther away from the focus. Since the distance between the focus and the output lens equals the focal length, this requires using a lens with a longer focal length.

The Keplerian design is typically not preferred for high-energy beams, such as the high-power pulsed laser beams used in some cutting and other manufacturing applications. Focusing pulses with nanosecond duration and optical powers around ~1 MW or higher, for example, can ionize the air and create a spark, which undesirably reduces the power of the pulse and can negatively affect the beam quality.

Characteristics of the Galilean Design

A basic Galilean telescope also includes two lenses, but one is negative while the other is positive (Figure 6). The lenses are positioned so that the distance between them equals the difference in their focal lengths, resulting in a more compact design than the Keplerian approach.

The Galilean approach can also be used to minimize the spherical aberration induced by the beam expander or reducer. All spherical lenses introduce spherical aberration, and one consequence is the spread of the beam focus along the optical axis. In the case of a positive spherical lens, parallel rays incident closer to the lens' outer perimeter focus to a point on the optical axis closer to the lens, compared with parallel rays incident near the lens' center. Since a negative spherical lens has the opposite effect, the negative lens in the Galilean design can be used to cancel out some of the spherical aberration induced by the positive lens.

When the device is used as a beam expander, the smaller-diameter beam is incident on the negative lens. The diverging beam provided by the negative lens increases in diameter as it approaches the positive lens, instead of focusing between the two lenses. This diverging beam can be described as having a virtual focus, which is located on the opposite side of the negative lens, as shown in Figure 6. Since the positive lens is one focal length

Expansion Ratio

Beam expanders and reducers are designed to accept and provide collimated beams. Although the beams are collimated, their diameters change as they propagate due to the effects of diffraction. Ideally, the input beam waist is positioned one focal length away from the input lens as shown in Figures 5 and 6. The output beam waist is then one focal length away from the output lens. If the input beam waist is not one focal length away from the input lens, the location of the output beam waist, the output beam waist diameter, and/or the divergence of the output beam may not match estimated values.

Both the beam's waist diameter

When the device includes two lenses, the formula for calculating the beam expansion ratio is the same for both Keplerian and Galilean designs. The beam expansion ratio equals the focal length of the output lens divided by the focal length of the input lens. The devices shown in Figures 5 and 6 are beam expanders when the light is incident on Lens 1, whose focal length is f1. In this case, the second lens (Lens 2) has focal length f2 and the beam expansion ratio

If the devices in Figures 5 and 6 are used as beam reducers, the light is incident from the opposite direction, upon Lens 2. Then, Lens 1 is the output lens, and the beam expansion ratio becomes m21 , which is f1 divided by f2.

Date of Last Edit: July 2, 2021

Insights into Best Lab Practices

Scroll down or click on one of the following links to read about practices we follow in the lab and things we consider when setting up equipment.

- Clamping Forks: Tip for Maximizing the Holding Force

- Optical Tables: Clamping Forks and Distortion of the Table's Surface

- Washers: Using Them with Optomech

- Electrical Signals: AC vs. DC Coupling

- Fiber Collimators: Tip for Mounting with Adapters

- How are the large mounting holes (counterbores) at the middle of a translation stage used?

- Is fast access to all mounting slots on a linear translation stage possible?

- What are some first steps to improving power measurements of low-power optical signals?

Clamping Forks: Tip for Maximizing the Holding Force

Click to Enlarge

Figure 2: More than half the total applied force (FTotal ) holds the object, since L1 > L2. The height of the left leg of this CL2 clamp is variable to compensate for the object's height. This allows the clamp's top surface and the mounting surface to be made parallel.**

Click to Enlarge

Figure 1: Less than half the total applied force (FTotal) holds the object, since L1 < L2. The clamp illustrated above is the CL5A.

Clamped objects can be fairly easy to move when the torqued screw in the clamp's slot is positioned too far from the object. Correct positioning of the screw protects clamped objects from being knocked out of position.

To maximize the clamping force, position the screw as close as possible to the object.**

This works since clamps like CL5A and CL2 (Figures 1 and 2, respectively) divide the torqued screw's applied force (FTotal) between two points.

Clamping force F2 is applied to the object. The value of F2 is a percentage of FTotal and depends on L1 and L2, as described below. The remainder (F1) of the total force is applied through the opposite end of the clamp.

The following equations can be used to calculate the two applied forces.

|

Force Applied to the Other Contact Point: |  |

These equations show that the clamping force on the object increases as the distance between the object and screw decreases. The force supplied by the torqued screw is evenly divided between F1 and F2 when L1 and L2 are equal.

**Note that maximizing the clamping force also requires both the top surface of the clamp and the area it contacts on the object to be parallel with the mounting surface, as depicted in Figures 1 and 2.

If the tangent at the interface between the clamp and object is not parallel to the mounting surface, the force applied to the object will be divided between pressing it into and pushing it across the mounting surface. The force directed along the mounting surface may, or may not, be sufficient to translate the object.

To accommodate different object heights, clamps like the CL2 have one threaded, variable-length leg, which is shown on the left in Figure 2. The number of threads between the clamp and mounting surface should be adjusted to compensate for the height of the object and to keep the clamp's top surface level with the table.

Date of Last Edit: Dec. 4, 2019

Optical Tables: Clamping Forks and Distortion of the Table's Surface

Click to Enlarge

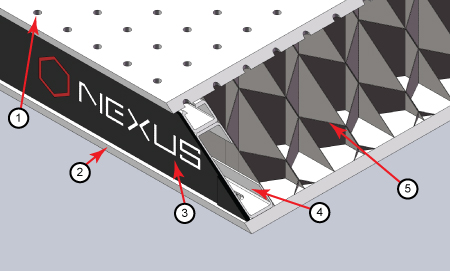

Figure 3: The construction of a Nexus table / breadboard includes a (1) top skin, (2) bottom skin, (3) side finishing trim, (4) side rails, and (5) honeycomb core. The stainless steel top and bottom skins are 5 mm thick.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 5: Torqueing the screw creates a force that pulls up on the table's top skin. The lifted skin tilts the mounting surface and can induce angular deviation of the object. This effect is exaggerated in the above image for illustrative purposes.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 4: A standard clamping fork, such as the CL5A, contacts the table along only one edge. The opposite edge is in contact with the object to be secured. A bridge forms between the two. The screw that applies the clamping force is not shown.

Click to Enlarge

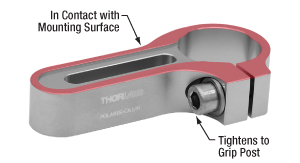

Figure 6: The POLARIS-CA1/M clamping arm has a slot that accepts a mounting screw, a separate screw that applies a clamping force to an installed post, and identical top and bottom surfaces. Since a nearly continuous track around the surface of the clamping arm is in contact with the mounting surface, clamping arms cause negligible bridging effects.

Clamping forks are more rigid than the mounting surface of composite optical tables. It might be expected that the spine of the clamping fork would bend with the force exerted by the screw as the torque is increased. Instead, the screw will pull the skin of the table up and out of flat before the clamping fork deforms. Due to this, clamping forks should be used with care when securing components to optical tables. Clamping arms, which are discussed in the following, are alternatives to clamping forks that are less likely to deform the table's mounting surface.

Optical Table Construction

Optical tables and breadboards with composite construction (Figure 3) are designed to be rigid while providing vibration damping. The 5 mm thick, stainless steel top skin is manufactured to be flat, but a localized force can deform it. When the top skin is deformed, optical components will not sit flat, and optical system alignment and performance can be negatively affected.

Clamping Forks

Standard clamping forks are installed with one edge placed on the table's surface and the opposite edge on the object (Figure 4). Between these two edges, there is clearance between the bottom of the clamp and the surface of the table. This bridge makes it possible to use a single screw to both secure the clamp to the table and exert a holding force on the object.

When the clamp is secured by torqueing the screw, the screw pulls up on the top skin of the table (Figure 5).

As the torque on the screw increases, the top skin of the table rises. Not only does pulling up on the table surface risk permanently damaging the table, this can also disturb the alignment of the optical component the clamp is being used to secure. By lifting the table's skin, the mounting surface under the clamped object tilts.

Clamping Arms

Clamping arms, such as the POLARIS-CA1/M, shown in Figure 6, are designed to secure a post while minimally deforming the mounting surface.

The clamping arm in Figure 6 differs from clamping forks in two significant ways. One is the surface area that makes contact with the optical table, which is highlighted in red, and the other is the method used to secure the post.

The area in contact with the optical table makes a nearly continuous loop around the base of the clamp. The contact area is flat and flush with the table when the clamp is installed. The only break in the loop is a narrow slot in the vise used to grip the post.

This design uses two screws, instead of the clamping fork's single screw. One screw (not shown) secures the clamp to the table, and the other (indicated) is tightened to grip the post. Since one screw is not required to perform both tasks, it is not necessary for this clamping arm to form a bridge between the clamped object and the optical table.

Although the contact area is a loop, and not a solid surface, this clamp causes negligible distortion of the mounting surface. This is due to the open area inside the contact surface being narrow and surrounded by the sides of the clamp, which resist the force pulling up on the table.

Date of Last Edit: Dec. 4, 2019

Washers: Using Them with Optomech

Click to Enlarge

Figure 8: Install washers before inserting bolts into slots to protect the slot from damage. The rounded, smooth side of the washer should be placed against the slot, and the rough, flat side should be in contact with the bolt head. The smooth surface is designed to translate easily across the anodized surface, without harming it. The BA2 base is illustrated.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 7: The diameter of the washer is 35% larger than that of the bolt head. This results in over a six fold increase in overlap area with the slot of a BA2 base. By distributing the force of the bolt over a larger area, the washer help prevent gouging of the slot.

The head of a standard cap screw is not much larger than the major diameter of the thread (Figure 7). For example, a ¼-20 screw has a head diameter between 0.365" and 0.375" and the clearance hole diameter for the threads is 0.264".

When the screw is tightened directly through the clearance hole to secure the device, the force is applied to the edge of the through hole, often cutting into the material (Figure 7).

Once the material is permanently deformed, the screw head will want to fall back into the gouged groove, thereby moving the device back to that location when attempting to make fine adjustments.

A device with a circular through hole is not meant to translate around the screw thread so the deformation is not expected to be a problem.

However, a slot should provide the ability to secure the device anywhere along the length for the lifetime of the part. Using a washer distributes the force away from the slot edge to decrease the chance of deforming the slot and extending the lifetime of the part. Figure 7 illustrates the difference a washer can make. The contact area between the slot of a BA2 base and a 0.27" diameter cap screw is 0.010 in2. When a 0.5" diameter washer is used the contact area is 0.064 in2, which is over six times larger.

When using a Thorlabs washer, there are two distinct sides (Figure 8). One side is flat and rough and the other is curved and polished. The curved and polished side should be placed against the device, which has an anodized surface.

As the screw tightens, the screw head can force the washer to spin against the anodized coating.

If the flat side is pressed down against the anodization, the friction created by the rough flat side can scratch the anodized aluminum. However, if the curved side is facing down, the smooth surface has less friction leading to less scratches and extending the visual appearance of the device.

Date of Last Edit: Dec. 4, 2019

Electrical Signals: AC vs. DC Coupling

Click to Enlarge

Figure 9: The DC offset of a signal is its average value. Since the blue curve (AC Only) has an average amplitude of zero, it has a zero DC offset. The red signal (AC and DC) is identical to the blue, except the red signal has a non-zero AC offset. A DC coupling would pass the red signal unchanged. An AC coupling would remove the DC offset and attenuate low-frequency components of the signal.

When an instrument offers a choice between AC and DC coupled electrical inputs, it is not unusual for the DC coupling to be the better option for a modulated input signal.

AC and DC Couplings

AC and DC couplings are interfaces between the input signal and the rest of the instrument's circuitry.

A DC coupling, which is called a direct coupling, is essentially a wire connected to the signal input. This conductive coupling transmits all of the signal's frequency components, the DC as well as the AC. The red curve in Figure 9 has a non-zero DC component.

In an AC coupling, the key feature is a capacitor placed in series with the signal input. The capacitor functions as a high-pass filter and is sometimes called a blocking capacitor. AC couplings strongly attenuate the DC and low-frequency signal components. This capacitive coupling is used to remove the DC offset from the input signal, so that only AC components are passed. The blue curve in Figure 9 has only AC frequency components.

Use the DC Coupled Input When Possible

There are many reasons to prefer the DC coupled input. Its low-frequency response is very good, it allows the DC component of the signal to be monitored along with the AC, and it does not cause signal distortion since it does not affect the frequency content of the signal.

Use of the DC coupled input is recommended unless the DC offset is large or the filtering provided by the AC coupled input is required. One problem with a large DC offset is that it can reduce the resolution of the instrument to unacceptably low levels. In extreme cases, DC offsets can cause clipping and saturation effects.

Note that using the DC coupled input does not guarantee a signal free of distortion. Distortion can occur due to other reasons, such as insufficient device bandwidth or impedance mismatch at the termination.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 11: Some modulated signals, including the blue curve plotted above, have no DC component, but they do have non-negligible low-frequency components. When this signal is high-pass filtered by an AC coupling, the resulting signal is distorted. The green curve is one example of this.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 10: This frequency response magnitude plotted above models a capacitor-based high-pass filter. Its cutoff frequency (Fc) is 35 Hz, and it was used to filter the signal plotted in Figure 11. That signal has a repetition rate of 200 Hz.

Reasons to Use the AC Coupled Input

By rejecting the signal's DC component, AC coupling can reduce the total amplitude of the signal. This can increase the measurement resolution provided by the instrument, as well as overcome saturation and clipping problems. AC coupling provides good results when information is carried by high frequency signal components and low frequency components are not of interest. AC coupling can also be preferred when the application does not tolerate DC frequency signal components, as is the case for some telecommunications applications.

When Using the AC Coupled Input

If AC coupling is used, it is important to keep in mind that this coupling acts as a high pass filter and affects the frequency content of the signal.

As illustrated by Figure 10, this coupling does not just remove the DC offset, it can also attenuate low frequency components that may be of interest. Due to this, AC coupling can result in signal distortion. To illustrate the effects of high-pass filtering, Figure 11 plots a binary signal, with 200 Hz repetition rate, before and after it is filtered by the high-pass filter with 35 Hz cutoff frequency (Fc).

AC-coupled, digital telecommunications signals mitigate this problem by ensuring the signals are DC balanced, so that they have no DC offset. If the signals were not DC balanced, a series of ones could cause a sustained high signal level. This would introduce a non-zero DC level that would cause the signal to be affected by the capacitive filtering. The result could be bit errors due to high states being incorrectly read as low states.

Date of Last Edit: Dec. 4, 2019

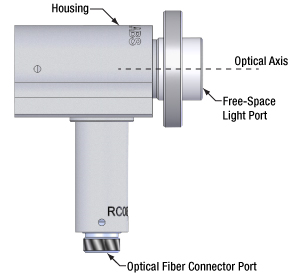

Fiber Collimators: Tip for Mounting with Adapters

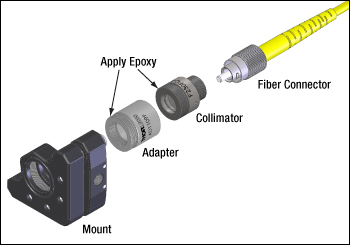

Click to Enlarge

Figure 12: The components shown above are joined using threaded interfaces. Since unscrewing the fiber connector could unintentionally loosen connections between the other components, Thorlabs suggests applying epoxy to the other two interfaces to immobilize them.

Fiber collimators are often used to introduce light into an optical setup from a fiber coupled source. Thorlabs offers a variety of fiber collimator packages, some only provide a smooth barrel (like the triplet collimators) and others have a metric thread at the end of the barrel (like the asphere collimators).

For both packages, Thorlabs typically suggests the use of an adapter with a nylon tipped set screw that holds the barrel against a two line contact.

Adapters for the external thread are available (AD1109F) that allow the user to thread the fiber collimator into a mount.

However, the use of these adapters results in a stack up of threaded interfaces (threaded fiber connector, threaded collimator, and threaded adapter). As a result, it is possible that unscrewing the fiber connector could inadvertently loosen another thread interface and create an unknown source of instability in the setup.

For this reason, Thorlabs suggests epoxying the threaded fiber collimators into the threaded mounts if that mounting mechanism is preferred.

Date of Last Edit: Dec. 4, 2019

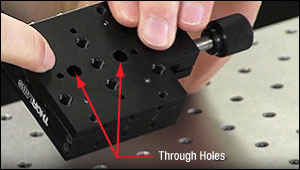

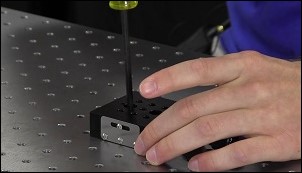

How are the large mounting holes (counterbores) at the middle of a translation stage used?

The mounting points used to secure some translation stages to a table or breadboard are located closer to the middle, rather than the perimeter, of the stage. Securing and releasing the stage from the mounting surface requires centering the top plate over the bottom (base) plate. When this is done, the oversized through holes on the top plate form a counterbore with the smaller through holes on the bottom plate.

Cap screws can then be inserted through the oversized holes in the top plate and screwed into the mounting surface to secure the stage. This is demonstrated using an MT1B linear translation stage. The stage can be released by loosening and removing the screws via the same holes.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 14: The two large through holes on the top plate of the stage provide access to the mounting points on the bottom of the stage.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 13: Through holes near the center of the stage's bottom plate are mounting points used to secure the stage to an optical table or breadboard.

Video Clip 1: The procedure for securing an MT1B linear translation stage to an optical table is demonstrated in this video clip.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 15: Each large through hole on the top surface of the stage provides the tip of a 3/16" (5 mm) ball driver access to the 1/4"-20 (M6) cap screws, which were previously inserted and used to secure the stage to the mounting surface.

Accessing the Mounting Points

The mounting points (Figure 13) are through holes located in the base plate, which is part of the stage's fixed world. The diameters of these through holes are large enough to pass the threads, but not the heads, of 1/4"-20 (M6) cap screws. Access to these mounting points is via the larger through holes (Figure 14) in the top plate, which is part of the stage's moving world.

However, accessing the mounting points requires aligning the top and bottom plates. The adjuster can be used to translate the top plate into alignment, so that each large through hole in the top plate is concentric with a smaller through hole in the bottom plate, forming counterbores. If a cap screw is inserted, threads first, into one of the through holes in the top plate, it should be possible to guide the threads through the hole in the bottom plate.

Secure the Stage First, then Mount Components

After the top and bottom plates are aligned, place the stage on the table or breadboard with the base plate in contact with the mounting surface. Align the counterbores with the threaded holes in the mounting surface, then insert a 1/4"-20 (M6) cap screw, from the top of the stage, into each through hole and then screw it into the table (Figure 15).

Since the top plate translates relative to the base plate, the top plate blocks access to the mounting points in general use. In addition, components mounted on the stage typically cover one or both of the through holes on the top plate. Due to this, it can be inconvenient to relocate the stage in the middle of an experiment. It is recommended that the stage be secured in an optimal location before mounting components on it.

Alternatively, a base plate like the MT401, which is designed for the MT stages, can be used to provide unobstructed mounting points at the perimeter of the stage. The stage is secured to the base plate as described here, and then the mounting slots on the base plate are used to secure the stage to a mounting surface.

Watch the Procedure Demonstrated

The procedure is demonstrated in the video clip (Clip 1), and the full video includes additional Insights on translation stages, including the procedure for replacing its adjuster screw with a motorized actuator.

Date of Last Edit: Sept. 8, 2020

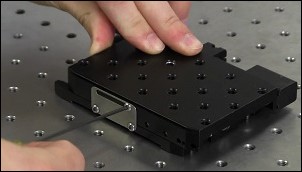

Is fast access to all mounting slots on a linear translation stage possible?

When a linear translation stage includes mounting slots at all four corners of the base plate, the position of the top plate usually blocks access to at least two of the mounting slots. A fast way to access all four slots, in pairs, is to retract the micrometer or actuator to expose two of the mounting slots, and then manually push the top plate into an extended position to expose the other two mounting slots. The top plate should then be held in the extended position by tightening the locking screw on the locking plate. This is demonstrated using an XR25P linear translation stage.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 17: This perspective provides a view of the rectangular and slotted locking plate attached to the side of the stage opposite the micrometer. The image also shows that the top plate overhangs the two mounting slots at the back of the stage, blocking those slots when the slots at the front of the stage are exposed.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 16: When the micrometer is completely retracted, the two mounting slots on one side of the stage are accessible. Each mounting slot accepts a 1/4"-20 (M6) cap screw and washer. The two mounting slots on the other side of the stage are blocked by the top plate.

Video Clip 2: The procedure for securing an XR25P linear translation stage to an optical table is demonstrated in this video clip.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 18: The top plate can be quickly pushed from a retracted position into an extended position, providing access to the other two mounting slots. Tightening the locking plate's screw with a 5/64" (2 mm) hex key will hold the top plate in position.

Retract the Micrometer to Access Two Slots

The four counterbored mounting slots used to secure these stages to an optical table or breadboard are integrated into the bottom (base) plate of these stages. Centering the top plate (moving world) over the base plate (fixed world) blocks access to all four mounting slots. Different pairs of mounting slots can be accessed when the top plate is retracted or extended.

To quickly access to all four slots, first retract the top plate using the micrometer or other adjuster. This exposes two of the mounting slots and makes it possible to secure or loosen a 1/4"-20 (M6) cap screw and its washer in each slot (Figure 16). As shown in Figure 17, the top plate overhangs and blocks the mounting slots on the other end of the stage in this position.

Push and Lock the Top Plate to Access Other Slots

If the top plate is in a retracted position and the base is held stationary, the top plate can be manually pushed into an extended position against the internal spring force. Do not let go of the top plate. If it is released, the spring force will propel the top plate backwards until it collides with the mechanical stop, which can damage the stage.

Push the top plate just far enough to expose the mounting slots on the back of the base plate, and then tighten the screw in the locking plate (Figure 18) to hold the top plate into position. With the top plate immobilized, 1/4"-20 (M6) screw and washer pairs can be installed in or removed from the newly accessible mounting slots.

Protect the Stage from Damage

When finished, hold the top plate to resist the spring force while loosening the screw in the locking plate. Slowly ease the top plate into its rest position to avoid causing a collision, whose mechanical shock can misalign the stage's components, affect the ball bearings, and introduce angular deviations to the stage's travel.

Watch the Procedure Demonstrated

The procedure is demonstrated in the video clip (Clip 2), and the full video includes additional Insights on translation stages, including the procedure for replacing its adjuster screw with a motorized actuator.

Date of Last Edit: Sept. 8, 2020

What are some first steps to improving power measurements of low-power optical signals?

Measurements of low-power optical signals can be improved by minimizing ambient light, blocking reflected and scattered light from reaching the power sensor (photosensor), ensuring the beam spot remains within the sensor's active area, optimally configuring the power meter's dynamic range, and performing the power meter's zeroing operation under ambient light conditions. The objective is to minimize the influence of spurious light sources on the power measurement, ensure that the sensor continuously measures the power delivered by the entire beam, and optimally configure the power meter for the experimental conditions.

Ambient Light

Ambient light is the light provided by all sources other than the optical system's light beam(s). In many cases, room lights are the greatest contributor to ambient light, but significant amounts can come from computer screens and other monitors, as well as light emitting diode (LED) indicators on instruments. A frustrating aspect of ambient light is that it can vary with the movement of the operator during the measurement, blinking of indicator lights, and screen display changes.

The effects of ambient light can include artificially inflating power readings, interfering with the detection of low-power signals, and saturating the sensor. When the sensor is saturated, the sensor outputs a signal near or at the maximum possible level. A sensor saturated by ambient light either cannot respond, or will respond poorly, to the additional power in the incident optical signal. The desired signal may also be undetectable if ambient light levels are low enough to avoid saturation, but high enough that the signal's contributed optical power is negligible in comparison.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 19: In the setup shown above, an SM1 lens tube is attached to the S130C optical power sensor, with the assistance of an SM1A29 thread adapter. The power sensor is positioned so that the exposed end of the lens tube nearly touches the transmission side of the nearest optical component. The lens tube helps isolate the power sensor from unwanted light. In a Video Insight, this setup was used to demonstrate a method for aligning a polarizer to be 45° to the plane of incidence.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 21: The beam spot can move across the power sensor due to alignment or normal operating conditions. The entire beam must be within the active area of the power sensor to accurately measure power. Circular movement of the beam spot during the measurement is illustrated above by the dashed-white circle. Ideally, the beam spot remains within the active area of the sensor (right). If the beam occasionally extends off of the power sensor (left), it can be hard to figure out that the associated power readings are artificially low.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 20: The front and back faces of the optic illustrated above are not parallel. Rotating the optic around the optical axis changes the direction of the transmitted beam. This type of situation can result in inaccurate measurements of optical power, as illustrated in (Figure 21).

Options for minimizing ambient light include turning off the room lights, installing the setup in a light-tight enclosure, covering monitors or turning screens to face away from the sensor, and / or turning off LEDs or covering them with black tape. Attaching a lens tube to the sensor housing as shown in Figure 19 can also be effective in reducing the ambient light incident on the power sensor.

Stray Light

Light beam(s) in the system can scatter, refract, and / or diffract from optics and mechanical housings in a setup, producing stray light. Stray light paths can be difficult to predict and block, since this light may interact multiple times with different optical elements and overlap the primary beam path. The effects of stray light on the measurement of the desired signal are similar to the effects of ambient light.

The best approach for blocking stray light depends on the beam trajectory and the setup, and often a combination of techniques are used. It is easiest to eliminate stray light that does not follow the beam path. Reflections can be directed away from the optical path by rotating optical surfaces away from normal incidence with the incident beam. However, this is only an option when the application is not sensitive to the optic's nonzero angle of incidence.

When the angle between the signal and stray light paths is reasonably large, a lens tube attached to the sensor (Figure 19) can block the stray light. If there is only a small angular difference between the stray light and signal paths, one option is to position an iris in front of the sensor to block the stray light while allowing the desired signal to pass through. Another option is to move the sensor farther away. With enough distance, the separation between the desired signal and the stray light will increase such that the stray light will either no longer be incident on the power sensor or will contribute negligibly to the power measurement.

Power Sensor Size and Beam Walk Allowance

The measured signal power will be artificially low if the diameter of the signal beam is larger than the active area of the power sensor. Note that the 1/e2 beam diameter, which is typically measured and specified for Gaussian beams, includes ~86% of the beam power. The diameter that encloses 99% of the beam power is a factor of ~1.5 larger than the 1/e2 diameter.

Ideally, the beam would be aligned so that it is centered on the active area of the sensor. If the beam is not aligned with the sensor's center, the risk of measurement errors increases. The power measurement will be low if the beam spot extends beyond the sensor's active area. If part of the beam overlaps with the active area, it may not be immediately obvious that there is a problem, since some signal power will be measured. Due to this, checking the overlap is recommended before taking measurements.

Imperfect overlap between the beam and power sensor might be a transient problem if the beam spot on the power sensor does not remain completely stationary during the measurement procedure. For example, the beam spot may wander if the measurement requires rotating an optical component around the optical axis (Figures 20 and 21). This is a particular concern if the front and back faces of the optic are not normal to the beam path. It may be possible to accommodate a moving beam spot by choosing a large-area power sensor.

Signal Within the Power Sensor's Dynamic Range

The sensor's dynamic range refers to the span of incident optical powers, minimum to maximum, compatible with the sensor. An accurate measurement requires the signal power to be within the sensor's dynamic range.

The noise floor typically defines the minimum detectable optical power level. The noise floor is the signal power reported by the power meter when absolutely no light is incident on the power sensor. The signal results from noise in the complete detector system, which includes the power sensor, power meter, cables, amplifiers, filters, and all other components. The incident signal will not be detected unless its optical power is sufficient to provoke a response exceeding the noise floor. Measurement accuracy may be poor when the signal response is close to the noise floor. A signal that is close to the noise floor has a low signal to noise ratio (SNR), which is the power in the desired signal divided by the noise power.

Power sensor manufacturers often specify maximum incident power levels below a threshold called the saturation intensity. Operating well below the saturation intensity threshold is recommended, since as the threshold is approached the sensor response becomes nonlinear and can result in power measurements that underestimate the power incident on the sensor. This can result in beam powers that unintentionally exceed applications' maximum operating power limits and is a significant concern. In the case of incident powers above the saturation intensity, the measurement reading is often a constant maximum value. One way to check for saturation conditions is to increase the signal power slightly while monitoring the power reading. If the reading remains constant, or changes much less than expected, it is likely that the sensor is saturated.

Zero the Power Meter to Ambient Light Levels

Set the zero value with the desired signal blocked from reaching the sensor, but without covering the power sensor. This can be done by blocking the signal at the source using an integrated shutter, if there is one, or by placing a beam block directly in front of the source. It is important that the beam block is not placed too close to the sensor, since during the zeroing procedure the power sensor should be exposed to the full ambient light level that will be present during the measurement. When this is done, the contribution of the ambient light will be subtracted from the measurement. If the sensor is covered while being zeroed, the ambient light power will be added to the measurement of signal power.

Date of Last Edit: May 16, 2022

Insights into Collimating Light from Different Types of Light Sources

Scroll down to read about collimation and collimated beams. Collimation is used to reduce the divergence of light from narrowband laser sources with Gaussian beam profiles, as well as from broadband and white-light sources such as light emitting diodes (LEDs) and bulbs.

- Does collimated light maintain a constant beam diameter out to infinity?

- Is the beam spot output by a collimating lens an image of the lamp or LED source?

Does collimated light maintain a constant beam diameter out to infinity?

Ideally, collimated light would have a constant diameter from the lens out to infinity, but no physical collimated beam maintains exactly the same diameter as it propagates. The collimated beam's divergence, which is the rate at which the beam's diameter changes, depends on the properties of both the light source and the collimator. Due to this, the collimated beam from a broadband-wavelength source, such as a lamp or light emitting diode (LED), behaves differently than the collimated beam from a narrowband-wavelength source, like a laser.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 1: If a broadband-wavelength source, like a lamp or LED, is placed one focal length

Click to Enlarge

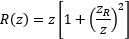

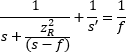

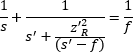

Figure 3: The input parameters in Figure 2 create a collimated output beam with a waist located a distance one focal length (50 mm) from the lens. Note that this figure's scale is larger than the scale in Figure 2. Close to the beam waist  )

)

Click to Enlarge

Figure 2: A 632.8 nm laser source, which has a 5 µm diameter waist (Wo) and a 31 µm Rayleigh range (zR), is collimated by a 50 mm focal length (f ) lens.

Click to Enlarge

Figure 4: The input laser light better resembles a point source when it has a smaller beam waist (Wo), and therefore a shorter input Rayleigh range (zR). The collimated output beam has a Rayleigh range (zR') that depends on Wo , focal length, and wavelength. Increasing the focal length, or decreasing the wavelength, increases zR' and decreases the overall output beam divergence. The values plotted above were calculated for a 632.8 nm wavelength and a focal length of 50 mm. For comparison, values for a wavelength of 1550 nm and a focal length of 25 mm have also been calculated.

Collimated Lamp or LED Light

An ideal point source emits light uniformly in all directions, and a positive spherical lens placed one focal length

θ ~ d / f ,

of the collimated beam. The better the physical source resembles a single ideal point source, the lower the divergence angle of the collimated beam (Figure 1). The resemblance is closer when the physical source is very small, far away from the lens, or both.

A Lamp or LED as a Good-Enough Point Source

A physical source adequately resembles an ideal point source when the divergence of the collimated output beam meets the application's requirements. If the divergence is too large, one option is to increase the focal length of the collimating lens, so the source can be moved farther away. However, this can have the negative effect of reducing the amount of light collected by the lens and output in the collimated beam.

In Figure 1, light emitted from each point on the source fills the lens' clear aperture. Rays traced from different points on the source show the output beam's diameter is smallest at the lens, and the beam appears to diverge from the clear aperture of the lens. If light from each point on the source filled only a fraction of the lens' clear aperture, the beam waist would be displaced from the lens.

Laser Point Sources

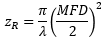

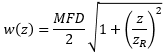

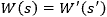

The point source model can also be adapted for laser light, but in this case the source is defined as the input beam waist. The source size is the waist diameter